- DEUTSCH

- ENGLISH

- SUCHE / SEARCH

The OLEANDER - a Time Traveler

In the blink of an eye of the Earth’s history, an oleander seed falls into a drop of tree resin. It remains there, entrapped, for millions of years and thus is preserved for posterity. The amber is the testimony to its existence in the place where the oleander plant once bloomed and bore fruit. So it happened in the Hukawang Valley, in the province of Kachin in northern Myanmar – a piece of Burmese amber from the Cretaceous period. (Burmese amber, Burmite, Wikipedia).

"The genus Nerium, whose best-known representative is N. oleander L. existed in Europe as early as the later Cretaceous period, and indeed was found in Central Europe as well as in Southern Europe at that time; it was still present during the Tertiary period also. Even during the earliest Tertiary period, a plant related to our current oleander existed in Southern France (Meximieux and Valentine), and Ferdinand Pax has recently described a Nerium bielzii from the Tertiary strata of Hermannstadt in Siebenbürgen [Transylvania] (Grundzüge Pflanzenverbr. Karpathen II (1908)23). On the basis of this fact, it is quite impossible that the oleander reached Europe only in historic times; the northern limits of its range were merely shifted southward as a result of the glacial period.” (Victor Hehn, Berlin 1870).

The WILD OLEANDER With Pink Blossoms

Like the blue sky and the sea, the hot sun, the scent of wild herbs and the shrill song of the cicada, the bright pink blossoms of the oleander have also been a component of the beauty of the Mediterranean landscape for two thousand years. But only in the 20th century did the appreciation for them enter into people’s consciousness. It was at that time, after the end of the Second World War, that mass tourism to the Mediterranean began. The South beckoned tourists with its light and color.

'Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühen . . .' ‘Do you know the land where the lemon trees bloom…’ [Goethe]. One hundred and fifty years ago, this journey to the south was only possible for the privileged bourgeois. They wrote of their impressions, raved about the beauty of the landscape, its flora and fauna, and thereby drew much attention to the pink-flowered oleander. However, the actual inhabitants of this region, who for thousands of years made their living by herding sheep and goats, feared the toxicity of this plant and destroyed it wherever they saw it in the landscape. And yet the plant survived the millennia . . .

"As with so many other plants of these regions, it hovered in the area between cultivation and wild stands; that is, once brought here, it was able to help itself and took on the appearance of a free child of Nature” . That is how even Pliny regarded it; at first he considered the small tree as native to Italy, but upon reflecting on the name, which is Greek: ‘‚Rhododaphni‘ or ‘Rhododendron’. . .“

"And then it spread throughout the countryside, as goats and donkeys (which usually leave nothing alone) avoid it, and from then on the oleander roses, like reddish gashes, illumined both banks of the watercourses streaming down the mountainsides of Southern Europe."

(The quotations are from 'Kulturpflanzen und Haustiere in ihrem Übergang aus Asien nach Griechenland und Italien sowie in das übrige Europa“ [‘Cultivated plants and Domestic Animals in their transition from Asia to Greece and Italy as well as to the rest of Europe’] by Victor Hehn, Erstaufl. 1870.) See also . .

With curiosity, we wonder when the ancient Greeks became acquainted with their „Rhododaphni“ (Rose laurel). As the writings report, neither Homer nor Alexander the Great were familiar with the oleander. But as Alexander and his army crossed the sandy expanses of Baluchistan, the Greeks encountered a plant which was similar to their ‘Daphni’ (laurel or bay). And then catastrophe ensued: the draught animals ate the plants and died.

Science later named this plant Nerium odorum, the oleander which adorned the wadis of the desert with bright pink, fragrant blossoms, but is extremely poisonous! This story, which has been handed down to us, gives evidence that the Greeks at that time were not familiar with the wild oleander in their homeland.

After the establishment of his empire, Alexander left his reports in the imperial archive in Babylon. Original documents were donated there to the learned world, but sadly these valuable pieces are lost. Evaluations thereof cannot be found in any literature either. An exception is Theophrastus’ History of Plants, which through the centuries has been the cornerstone of botany. For this reason, Theophrastus is also called “the Father of Botany”. The oleander appears here under the name “Oenothera” and is listed as a poisonous plant.

"The development of plant geography is one of the most significant scientific results of Alexander’s campaigns. Alexander the Great discovered for the old Western world a new one, the Eastern world; and plant geography, which depends so much on a survey of the most varied types of landscapes, was imbued with new life. What is invaluable is that Alexander himself, in the noble spirit of research, made sure that scientific descriptions of this new world would be recorded." - Excerpt from the book „Botanische Forschungen des Alexanderzuges“ (Botanical Research of Alexander’s Campaigns), by Dr. Hugo Bretzl, Leipzig 1903.

As was later recorded. The oleander in ancient Greece stood on the banks of rivers and seacoasts. There, where homage was paid to the sea god Nereus and his 50 daughters, the rose-like blossoms of the Rhododaphni were left as offerings on the altars of the nymphs and used in floral garlands.

Pedanius Dioskurides lived in the first century and was a Greek physician and pioneer in pharmacology. He was educated in Tarsus, the most significant center for botanical and pharmacological research in the Roman Empire. Contained in the oleander’s poison are toxic glycosides (cardiac glycosides). “Materia Medica” by Dioskurides lists approximately 1000 pharmaceuticals. (Vienna Dioskurides Codex, Vienna Dioskurides Codex in the Austrian National Library).

Around 40 AD, the Romans built their western administrative center of Mauretania on the ruins of a Carthaginian city. The population consisted of Berbers, Jews, Greeks, and Syrians, who until the arrival of Islam spoke Latin and were Christians. The name of the ancient city VOLUBILIS is related to the Berber word „Oualili" for oleander - the OLEANDER FLOWER that is common in the region. (Oualili, Volubilis - UNESCO World Heritage Site, History of Volubilis).

It’s fascinating to think that the oleander with its pink flowers wandered over mountains and valleys in the often desertlike landscape of North Africa, and for some thousands of years. Water sources lying deep below the surface played an important role in this.

As the volcano Vesuvius near Naples erupted in August 79 AD, a terrible tragedy unfolded. The terrain around Pompeii was buried under approximately 7 meters of ash layers and was thus forgotten until into the 18th century. Through excavations, Pompeii became a central object of archaeology and research into the world of antiquity. Frescoes there depict the oleander, and it can be documented that 100-year-old oleander trees decorated the gardens.

The bright pink blossoms of the oleander characterize the landscape around the Mediterranean Sea, as their annual masses of seeds are stirred up by the wind and urged to dance. Weightlessly, spinning on their little parachutes, the often fly over great distances to take root on the banks of wild watercourses. Frost is what sets the limit on these wanderings. The emerging seedlings are the exact image of their parents and proudly wear the pink flowers of the wild oleander.

In Crete, there once stood dense forests which were home to a rich fauna and flora. The vegetation of antiquity, which consisted of cypresses, cedars, pines, stone pines, and holm oaks, provided the wood for the Minoan fleet of trade ships and also for the sailing ships of the Venetian war fleet. As recorded, there were oleanders here as well, which grew upright into trees and whose clouds of pink blossoms brightened the valleys of the “White Mountains”. Today, the bare gray rock looms high in the blue sky, and deep chasms divide the massive rock formations, through which the myths of the past drift.

However, in mid-millenium – the year 1547 – the Frenchman Pierre Belon traveled in Crete and the Greek mainland. He documented flora and fauna; they are the first research chronicles in Greece. He was a pharmacist and was searching for medicinal plants. On Mount Ida, near the village of Kamaraki, Belon found an oleander with white flowers. This discovery was a sensation in the scientific world, as until then only pink-flowered oleanders were known.

Belon’s records are located in Paris today. Here is a translation from the original text:

“The Nerion with white flowers blooms in April on a mountain path near a village by the name of Chamerachi on the road from Candia. It is quite difficult to climb the mountain path on the western side, as the slopes are steep, almost as straight as a ladder. There at the foot of the mountain lies a village from which the steps begin; one counts 7,000 to reach the peak. It seems that the eastern part is milder than the other one, as the soil is very rich and moist all around the base of the mountain, where there are also a great many villages, and all sorts of things can grow well: fruit trees, grapevines, and olives; and in the fields all sorts of vegetables and grains are planted. “

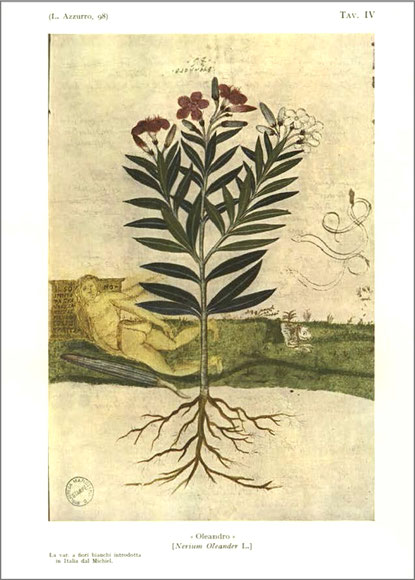

As recorded, the white oleander was brought by Pietro Antonio Michiel to Venice, where it was panted and propagated. By the end of the century, it was blooming in London as well.

In 1740 a “Grosses vollständiges UNIVERSAL LEXICON Aller Wissenschaften und Künste” (Great Comprehensive UNIVERSAL LEXICON of All Sciences and Arts) , published in Leipzig and Halle, reported the following: “Oleander - DEMON PLANT, as the plant is a harmful one which kills people and livestock, and therefore not friendly to man or beast. Rose tree, Rose laurel, Laurel rose, as the blossoms occur in the same colors as roses, but the leaves resemble those of the laurel . . . it almost looks the same as the laurel tree . .” What is described here is the pink-blooming Nerium oleander, which occurs in the wild all around the Mediterranean and is used for medicinal purposes. A white-blooming type is also mentioned.

In 1753 Carl von Linné, the father and pioneer of botany, created a classification system in which all animals and plants received their place in “Species Plantarium“. The system is valid even today and enables international comprehension. The oleander was assigned to the plant family Apocynaceae and placed in the genus Nerium, There is only one species, with the name “OLEANDER”.

In 1774, the “Onomatologia Botanica Completa“, the most compregenseive botanical dictionary, was published. In it, the following appears: „Nerium candidis floribus in montibus idea convalibus“ – An oleander with white blossoms grew in the Ida mountains – for BELONIUS this means a variant of the common oleander which has white flowers; the same pertains to C. Bauhin „Nerium floribus albis“.

In 1818. Gaetano SAVI in Italy reported:

"A variety with white flowers is grown; it was growing spontaneously in Crete on Mount Ida near Camerachi (Bellonio I., chapter. 16) and was brought to Italy in 1547. (Mattioli loc. Cit.) It retains its color even when propagated from seed, and I have never yet seen, nor do I know of anyone else who has seen white-flowered plants originate from the seeds of the usual Mazza von San Giuseppe.” (Staff of St, Joseph, = Mediterranean oleander).

Unfortunately, one can’t find any statement today regarding the natural occurrence of this white oleander variety, but it is certainly mentioned in old records as a garden plant.

In 1817 – about 270 years after BELON – the nature researcher/physician Franz Wilhelm Sieber travelled around the island of Crete and made a great scientific contribution with his botanical postings and illustrations ('Reise nach der Insel Kreta . .' – “Journey to the Island of Crete…”). He assisted in the role of a physician on his journey and described the life of the people, who, previously ruled by the Venetians, now had to live under the Turkish powers. During his explorations, he mentioned some of the settlements which he passed on the way to the location where the white oleander was discovered. They are in eastern Crete, between Ágios Nikólaos (St. Nicholas) and Sitía. These villages can still be found today! The beach which he mentioned can perhaps be connected with the fishing village of Móchlos – presuming a bit of imagination.

In his book, Sieber writes that the people there called this plant “Galanosphaca“ the “milk-white” oleander. If this is the case, it would have to be called “Galaktosphaca“ – an auditory error or a slip of the pen on the part of the author. We cannot find any account of a milk-white blossom. Does this perhaps refer to the poisonous milky sap which oozes from a cut?

In 1583, a Venetian census mentioned a village in this area with 244 inhabitants. The little town was named after the oleander - SFAKA. Today, this “Oleander Village” lies along E-route 75, which runs all the way from Norway to Sitía.

Thus we learn that the oleander, in the West just as in the East, was a “fixed star” in the huge forests of Crete, as:

In 1888. A Greek book told of the history of SFAKIA (SFAKIA, A history of the region . .). There, where the foothills of the White Mountains drop steeply into the Libyan Sea, lies one part of the region, and the other part of Chora Sfakia is nestled among the rocks at breezy heights. The oleander blooms abundantly here, and people call the plant “Sphaca“. It is possible that the region of Sfakia received its name that way. Hikers report that in the gorges of Aradena, one can still see tall oleanders, as well as vultures and eagles.

The flora and fauna of the Mediterranean landscape stir the interest of researchers, especially with regard to eastern Greece.

The physician and botanist John Sibthorp of Oxford began his great research journey toward the end of the 18th century. This was the first comprehensive description of Greek plant life.

1.000 drawings were transformed into precisely colored illustrations of flowers through the exceptionally gifted hand of the Viennese botanical illustrator Ferdinand Bauer. They have survived the centuries in the 10 volumes of FLORA GRAECA.

With the advent of ocean voyages, a new era began. It led to a success story for the oleander which could hardly be more exciting . . .

A new Oleander came from the expanses of Asia

The Diversity of the oleander emerged

Europe set sail, and the search for new worlds began. New plants were especially important for the medical field, as most of the native plant material had already been researched. Thus, the first traveling researchers were pharmacists and doctors; they got involved in the hunt for “green gold” and this search was to last for hundreds of years. The “plant hunters” brought an immeasurable wealth of new botanical treasures back to Europe. Thus, botany traces its origins back to the study of medicine and healing.

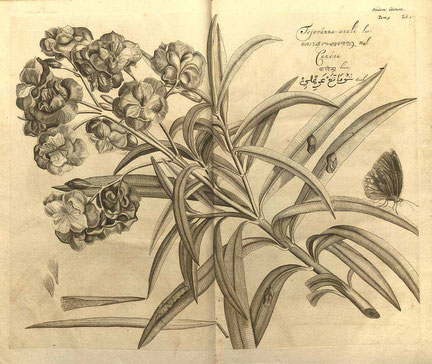

Oleander plants from India reached Europe. The first mention of “Nerium indicum’ and “Nerium latifolium” was in 1680 upon their arrival in Amsterdam. The plants came from Ceylon. Here is the corresponding illustration, drawn by Jan and Maria Moninckx.

HORTUS MALABARICUS the “Garden of Malabar“, contains the earliest writings regarding the flora of Asia and the tropics. It was written by Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede tot Draakenstein, the governor of Malabar over a period of 30 years (1678-1693). The books (12 in number) primarily provide information about the flora of the west coast of India, from Goa to Kanyakumari, and detail the flora of Kerala.

Jan Commelin (1629-1696) published this work. He was an independent merchant and led the wholesale trading of medicinal plants in Amsterdam, and soon a garden of medicinal plants as well which later grew into the „Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam“, one of the oldest botanical gardens of all. This was the threshold of importation of plants into Europe on an enormous scale. The Dutch East India Company alone was able to procure many unknown plants and seeds from its overseas possessions. In 1683, Commelin published the first book of the flora of the Netherlands under the title „Catalogus plantarum indigenarum Hollandiae“.

The collecting of plant material from around the world necessitated the creation of receiving stations. Here, this material was registered, researched, and further distributed. The first botanical universities and their gardens emerged as a result.

The oleander varieties which came to Europe from various regions of Asia over the course of time brought “the Indian blood” which can alter the flower shape and color as well as the form of seed pants. In addition to that, fragrance, which the flower of the Mediterranean oleander did not possess, was a new development. Scholars collected and described these new oleander cultivars over a long period of time. Today’s technology allows us to leaf through botanical records and plant lists from the past (Onomatologia Botanica Completa). A fascinating circumstance, when one considers how many wars and how much unrest was shaking Europe at that time.

Among paintings of flowers from that time, many beautiful oleanders are depicted (plantillustrations.org).

In 1819, the Imperial House of Habsburg ordered plates depicting oleander blossoms. These would later be used as dessert plates on the imperial table when it was set with the Grand Vermeil, the Silver Collection.

A particularly significant proof of of the popularity of the oleander is found in the portrait of the Empress Elisabeth of Austria (by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1865, with diamond stars) which shows oleander blossoms in the background. This high distinction can be regarded as the peak of the fashionability of the oleander in the 19th century.

In 1829, the work 'Vollständiges Handbuch der Blumengärtnerei' (The Complete Handbook of Flower Gardening) by J. F. W. Bosse was published. The listed oleander cultivars range from “Common” to “Indian” oleanders; single, double, and fragrant varieties are mentioned and various colors are described. He even indicates the nurseries where specific varieties could be obtained, and even some prices.

At almost the same time, in 1838, the book 'Deutschlands phanerogamische Giftgewächse in Abbildungen und Beschreibungen' (The Phanerogamic Poisonous Plants of Germany, in Illustrations and Descriptions ) by J. F. Brandt and J. T. C. Ratzeburg appeared. The plants – including the oleander - are described in almost unbelievable detail, along with comprehensive source information. However, not only its characteristics and appearance are described, but also pollination and seed planting. In the accompanying copper engraving, cross-sections of the blossom and the ovule are illustrated. The picture shows what great care is taken in raising the seed to the stage of a germinating seedling.

Also at the same time: a wonderful example of how much people cared about the diversity of varieties, about the new oleanders from “India”, during this epoch. Neues Handbuch des verständigen Gärtners, oder neue Umarbeitung des . . (New Handbook for the Knowledgeable Gardener, or a New Adaptation of . . ) J. F. Lippold, 1831.

In 1875 , Charles Cavallier published a description of the varicolored oleanders which were grown from seed in the garden of Monsieur Sahut in Montpellier, France. (Le Laurier-rose À Montpellier . . , French. / English translation by James Nicholas).

In the 1960s, as mass tourism to the Mediterranean began, we took home cuttings of the pink-blooming wild oleander; the plant served as souvenirs of our vacations. It stole the hearts of Central Europeans as a container plant and beautified terraces and balconies. Propagating this oleander from seed was certainly possible, but the result was disappointing. The flowers were always pink, as the plant was monotypic; i.e. the offspring always resembled their parents.

In the 1980s, the Munich nursery „FLORA Mediterranea“ surprised us with a selection of 50 different oleander cultivars, which in addition to pink, red, and white also included shades of apricot, salmon, and yellow. The growth habits and nuances of fragrance were varied. We call them the “modern oleanders” of our time, although they probably are the last of a multiplicity of varieties which were introduced and propagated centuries ago. Up to the present day, these multicolored new oleanders have been propagated by the millions through cuttings. Certainly far fewer have been propagated from their seeds, since there is no literature on the special, unique features which this form of propagation can produce. In all our ‘modern’ German gardening books – even on the internet today – there is no reference as to what fireworks in color and form are possible through seed propagation.

It is assumed that the botanists of the past crossed the different varieties of Indian oleanders with goals in mind. Artificial hybridization of the oleander, however, is complicated and labor-intensive.

Perhaps it had been observed early on that butterflies and moths, whose long probosces are able to reach down into the sticky and deep-lying nectaries, were good alternatives. (Bees remain unemployed here!)

The most beautiful moth, with its pink and green pastel coloration, is Daphnis nerii, the “oleander hawk moth”, whose fat grass-green caterpillar eats the foliage of the oleander. The hummingbird moth is also a guest we like to see, and reminds us of a hummingbird.

The more varied the selection of flowers, the greater the chance is for the birth of an excitingly beautiful new blossom. And – from every seed grows an individual new plant, a new cultivar, to which we can give a name. We can then propagate them through cuttings and thus preserve them.

About 30 years ago, the first oleander seeds were raised simultaneously in Hungary and Greece, without any of the parties involved knowing of the others’ efforts. We could all access seeds of the wild pink oleander, The result was seedlings whose blossoms were the same as those of the parent plants. In Greece at the time a double-flowered variety (a “Splendens type”, whose roots are in India) became a garden plant and spread rapidly. With the seedlings it produced, I established in amazement and excitement that their flowers were totally different than those of the wild oleander. There were similar experiences in Hungary.

Here, I believe, is the final proof that the Mediterranean oleander can hybridize and/or has hybridized with the Indian types, Our contemporary so-called commercial varieties are the end product of a spiral of diversity which has been spinning through the centuries. Today, many oleander enthusiasts – especially in Hungary – have embraced this method of propagation excitedly and thereby have set the “wheel of development” in motion again. In Hungary alone, there are thousands of new flower colors and forms; often different in shape and fragrant.

And if we keep in mind that each seed which ripens along with innumerable others in a single oleander pod can become a new oleander variety in form and blossom, then we can glimpse the unbelievable diversity of the oleander blossom in color, shape, and fragrance. But not only that, as the form of the plant can also change (dwarf growth habit).

The accompanying photo shows:

Differing colors and forms of seedlings from a single pod of the cultivar “Eurydike”

(The experiment is from Hungary)

And with that, the “weed plant” of the South makes its appearance with a new face. Where it was once uprooted and weeded out, it is now sought after as a hedge plant, for the median strips of highways, and as an ornamental plant in parks and gardens, as it blooms abundantly and in many colors under the hot sun of the summer months.

But what will the future look like? Will the new varieties assert themselves and multiply with the same vigor as the wild pink oleander once did? Or might one ask: has the oleander as a wild plant met its end?

January 2019, Irmtraud Gotsis

Translation by James Nicholas